Present tense: Leah Rosenberg’s Fresh Paint

Holy smokes! Looks like some sort of guest-host relationship to me.

—Laurie Anderson

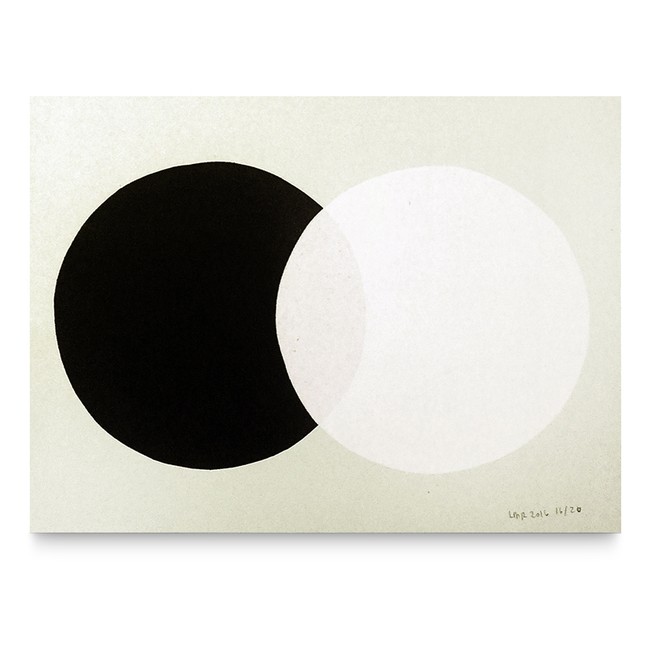

Cakes and paintings have more in common than might meet the eye (or the mouth, as the case may be). Both, for example, can embody pleasure, sharing, or even celebration. In both, time accrues in the form of layers—though, in paintings, often all we see is what’s on top, while cakes’ interiors are revealed in the very act of consumption.

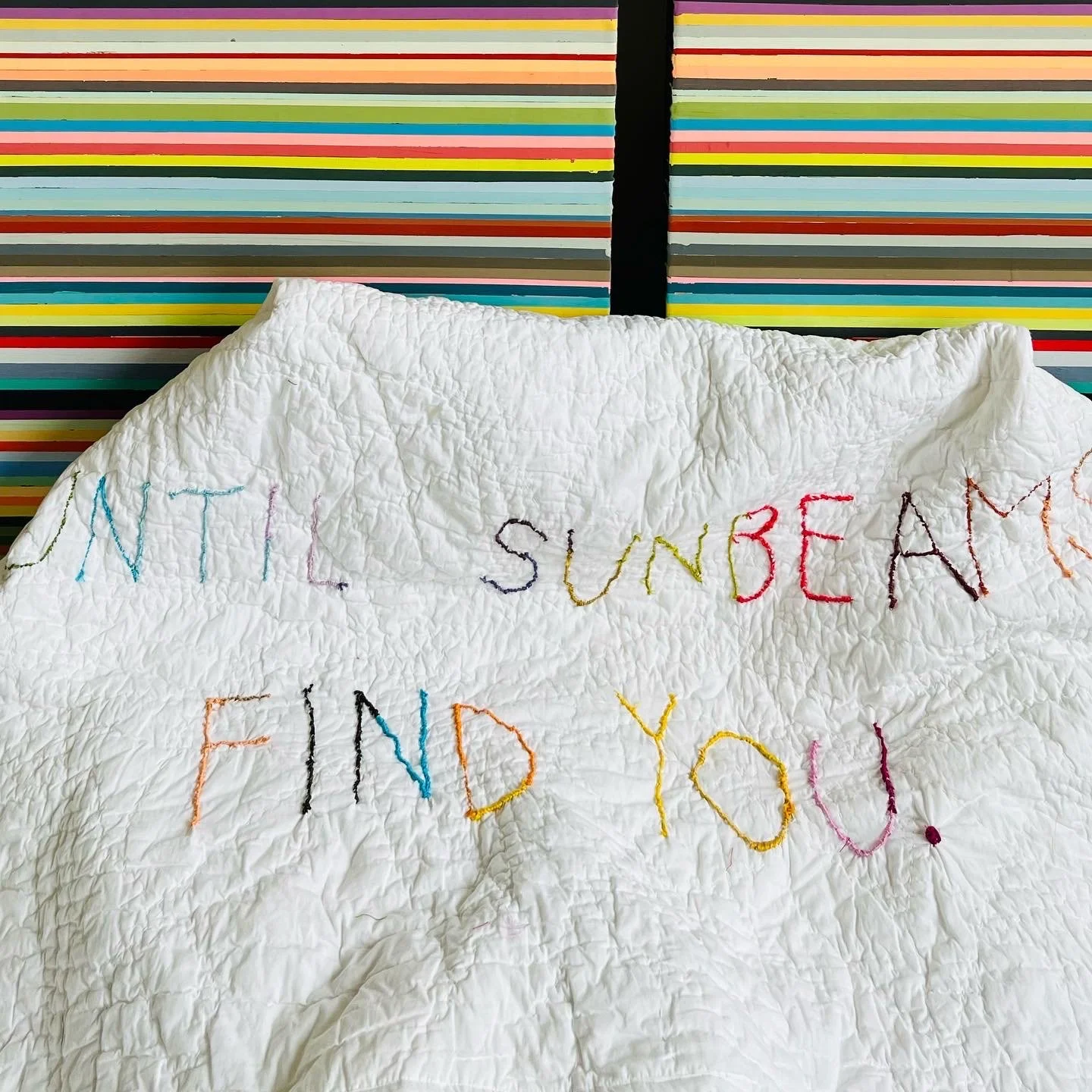

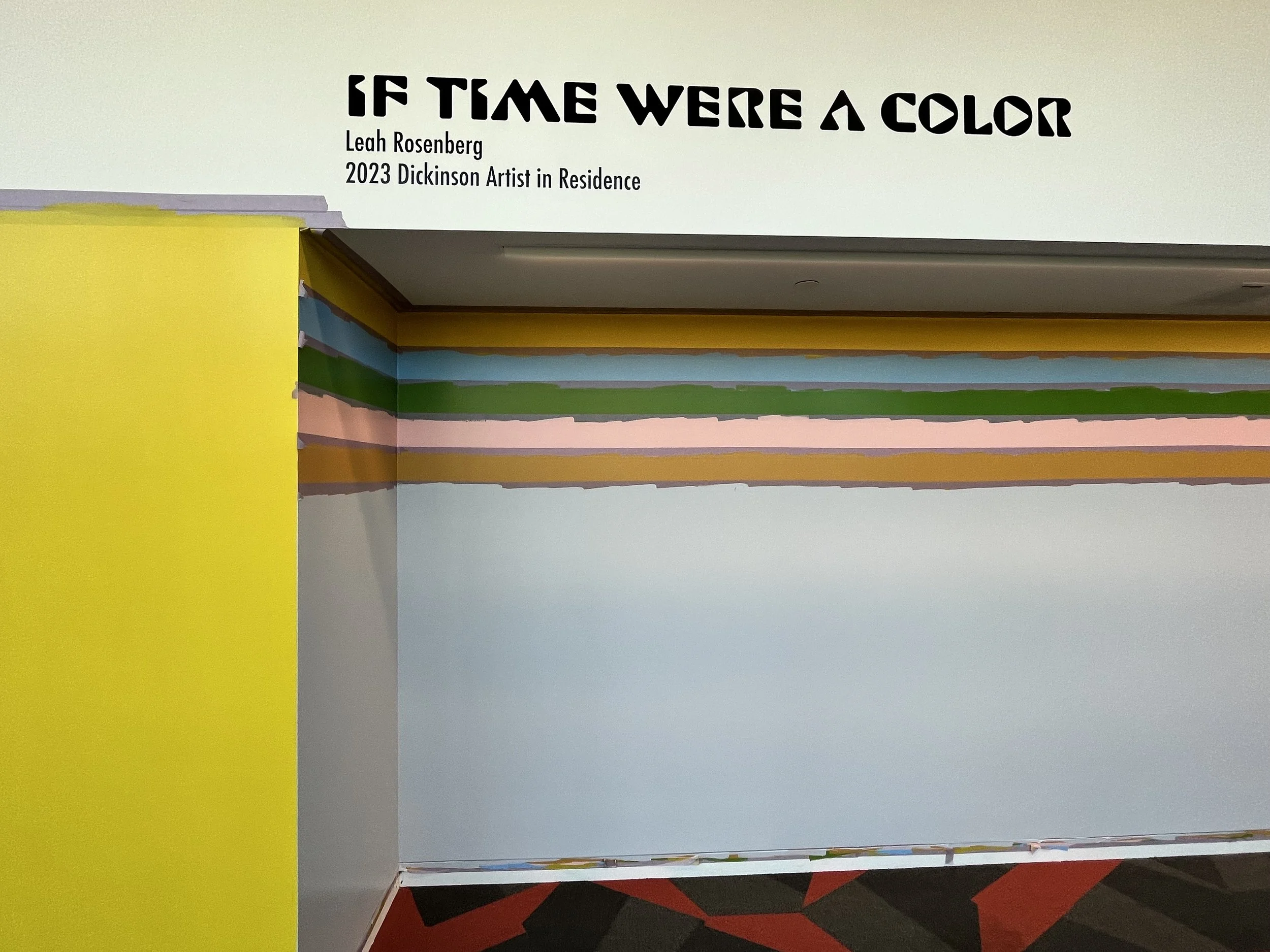

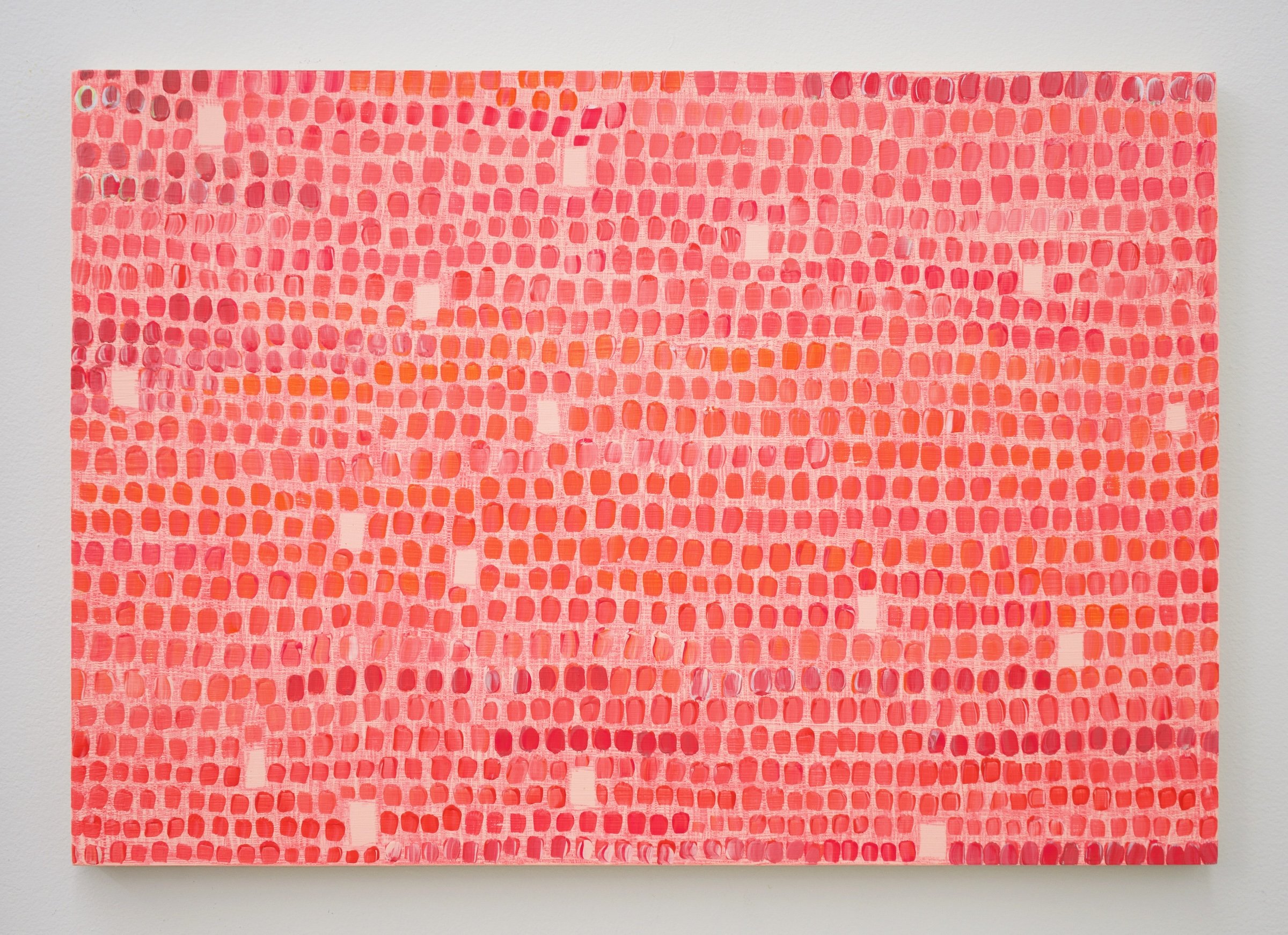

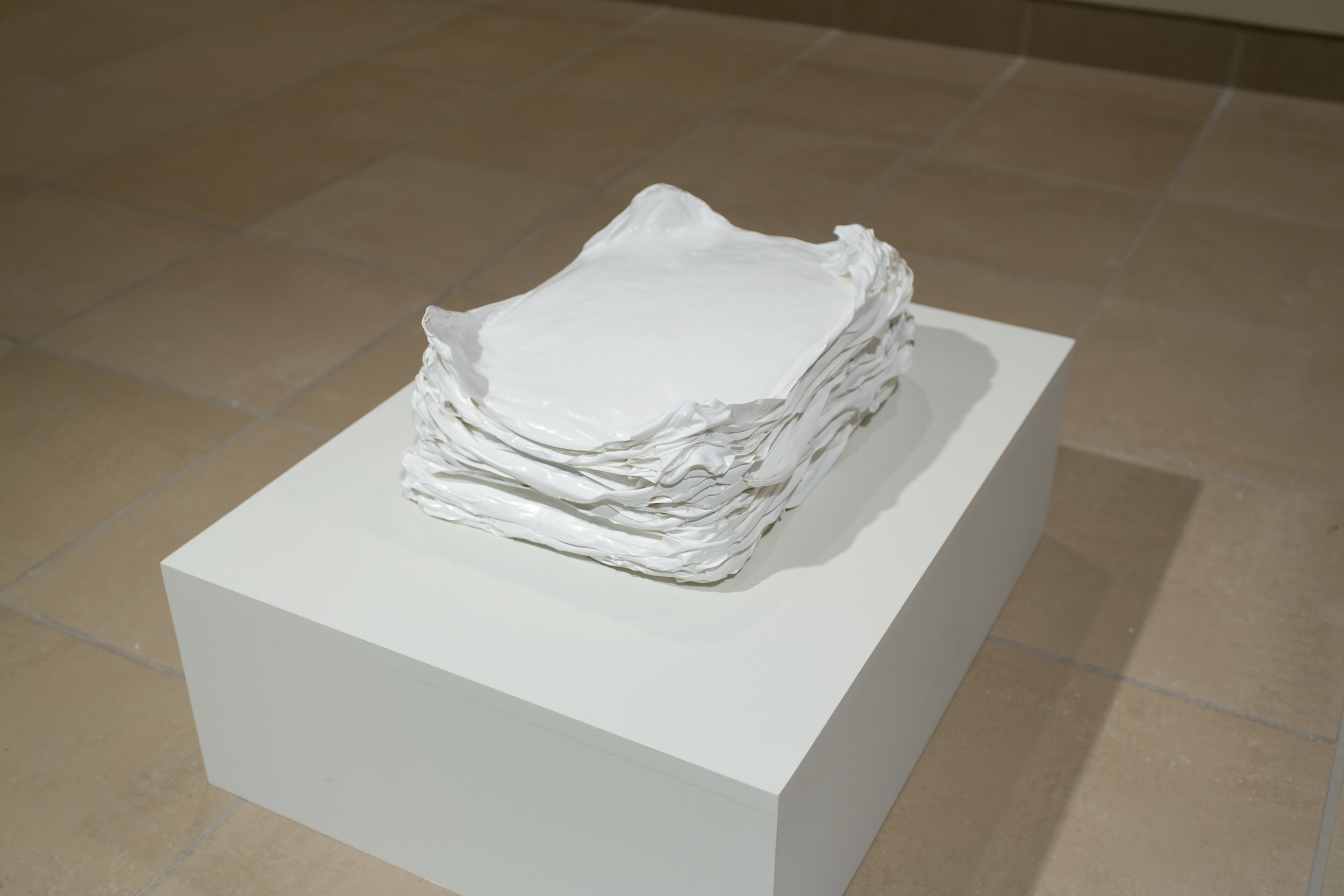

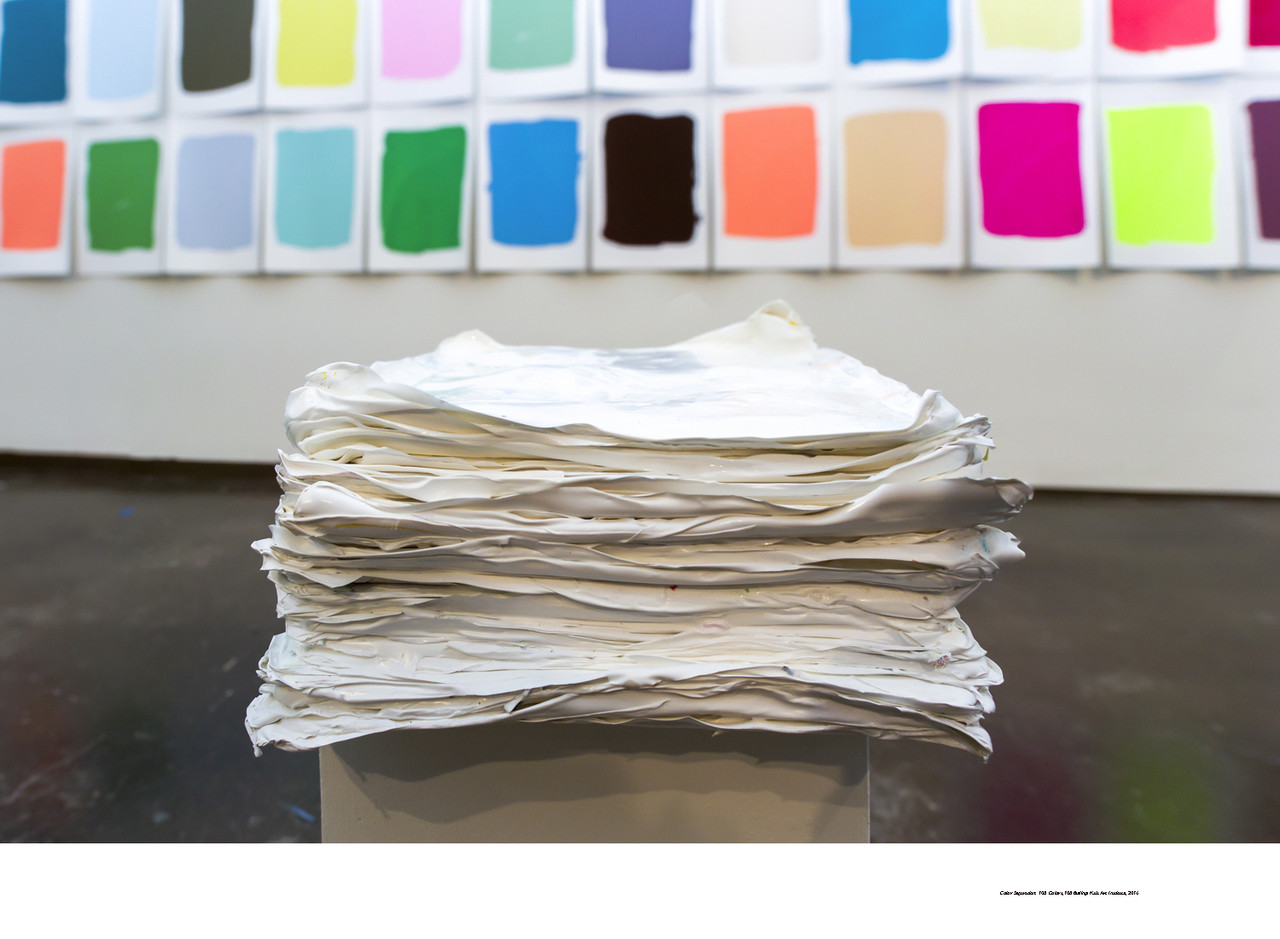

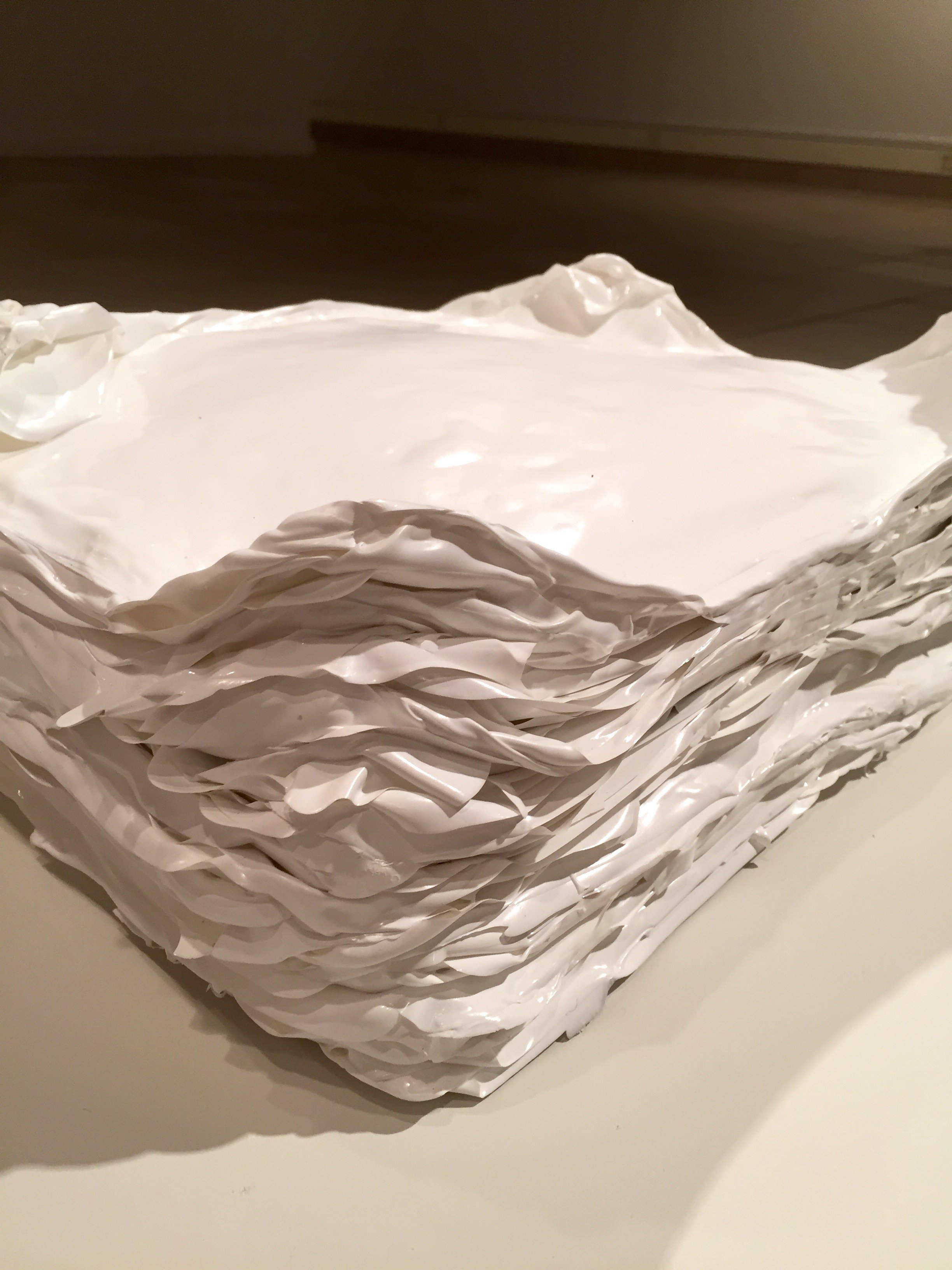

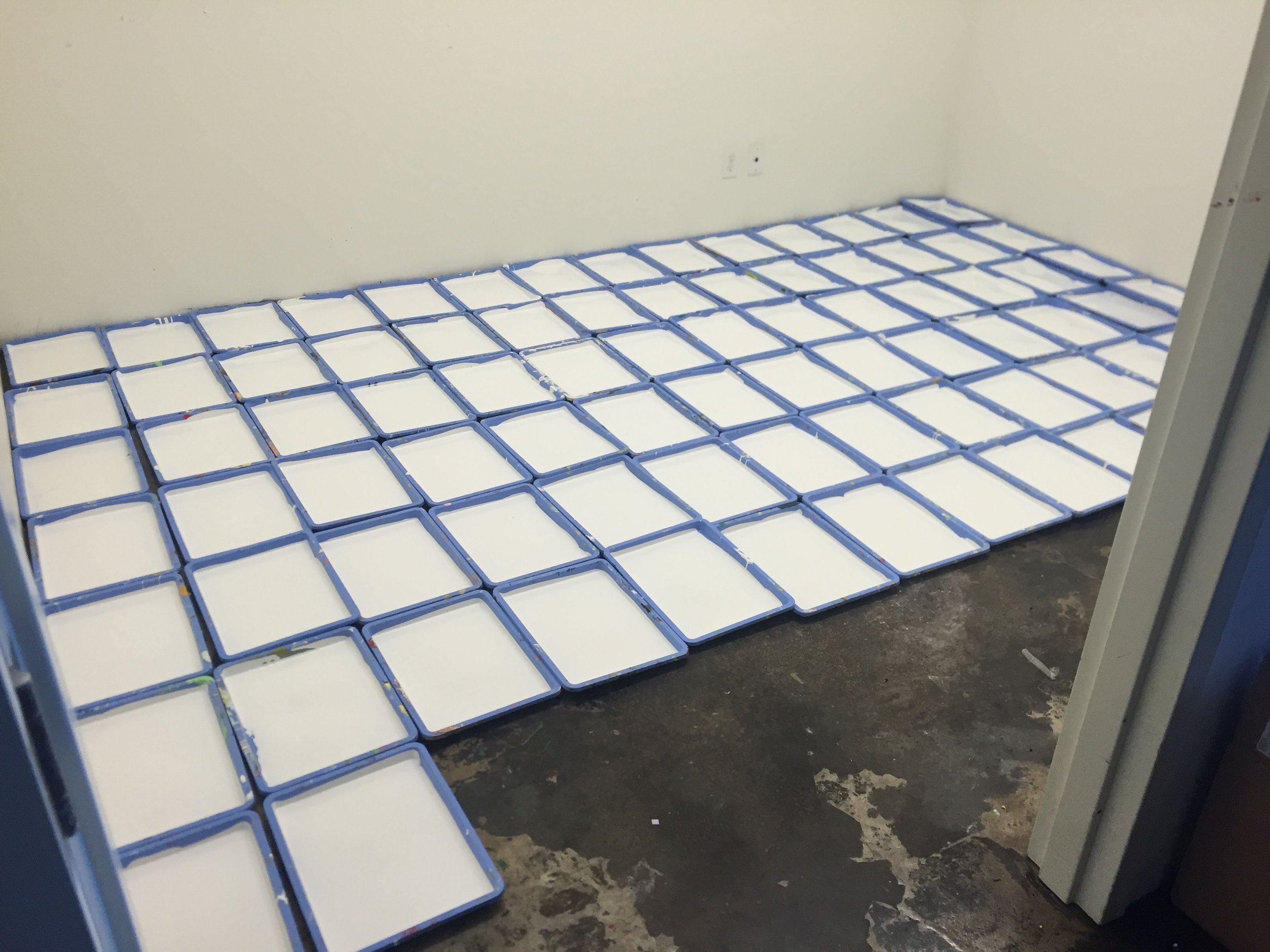

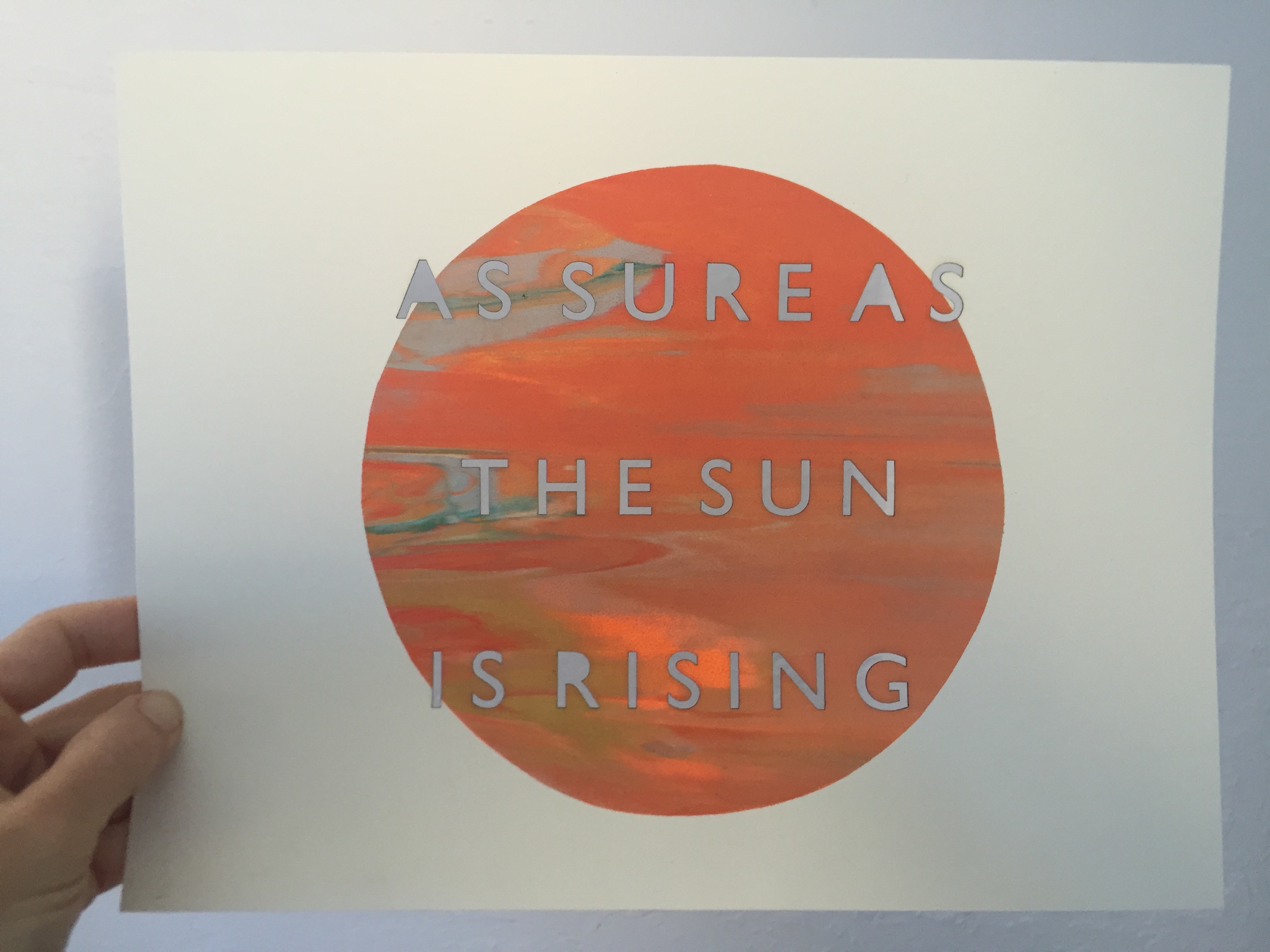

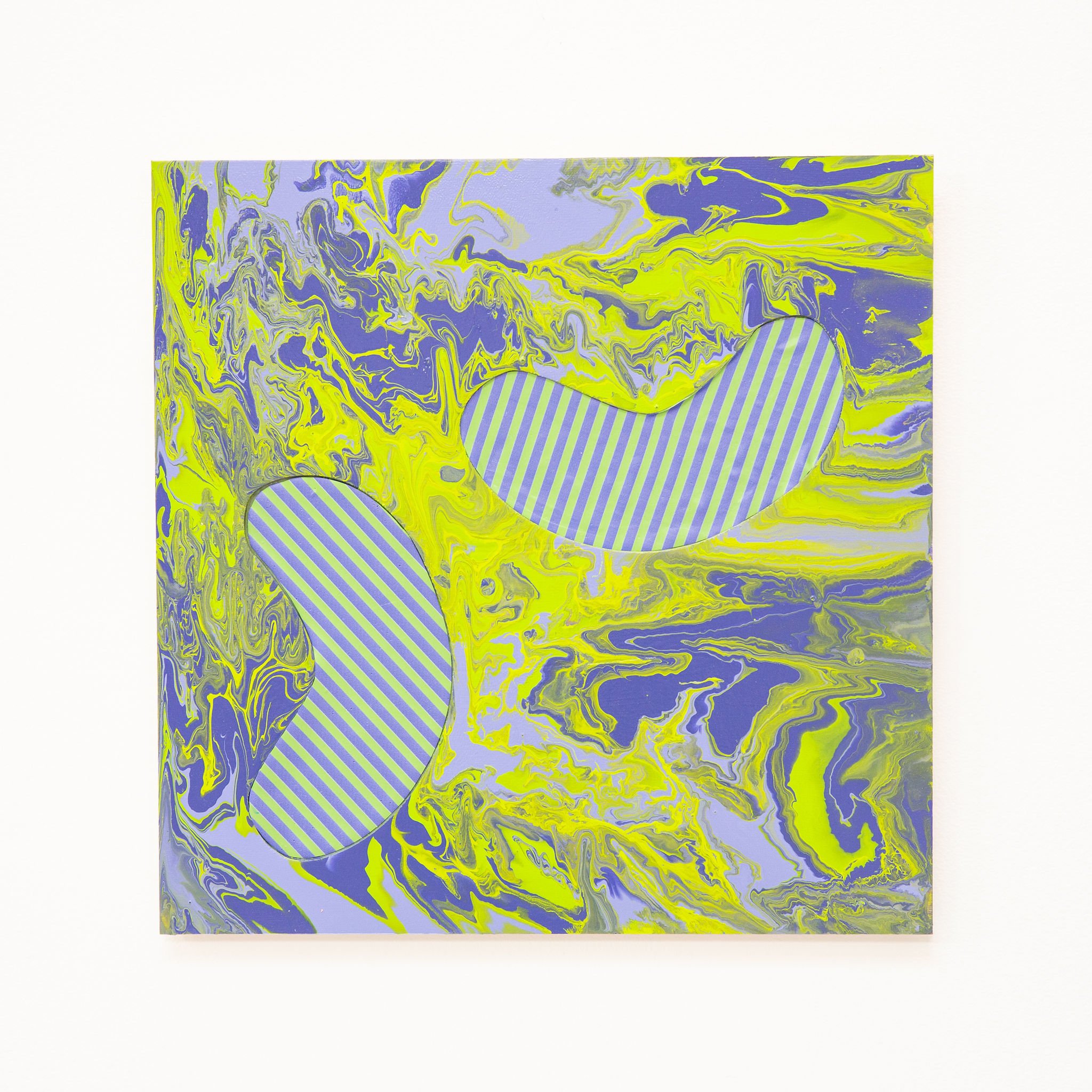

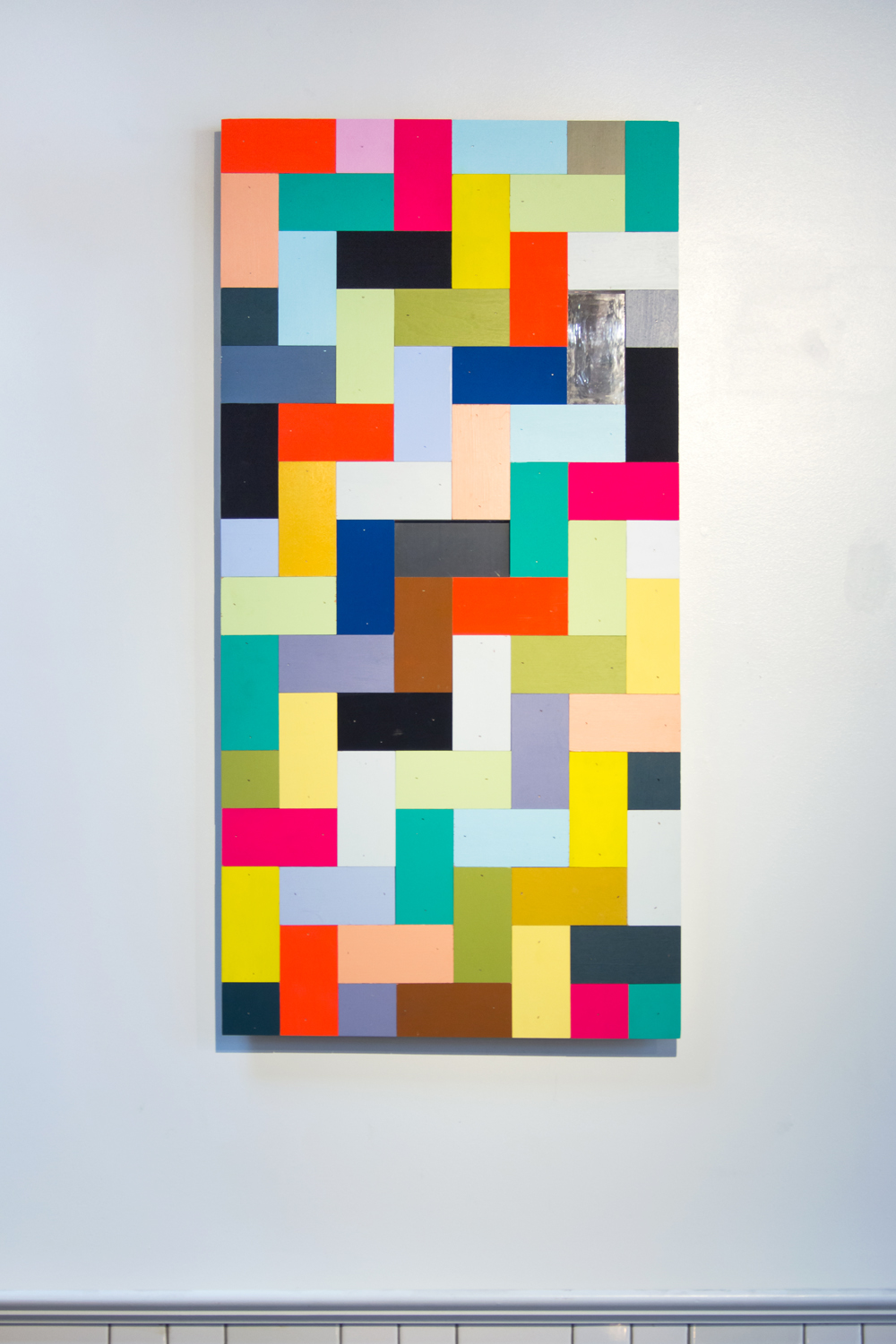

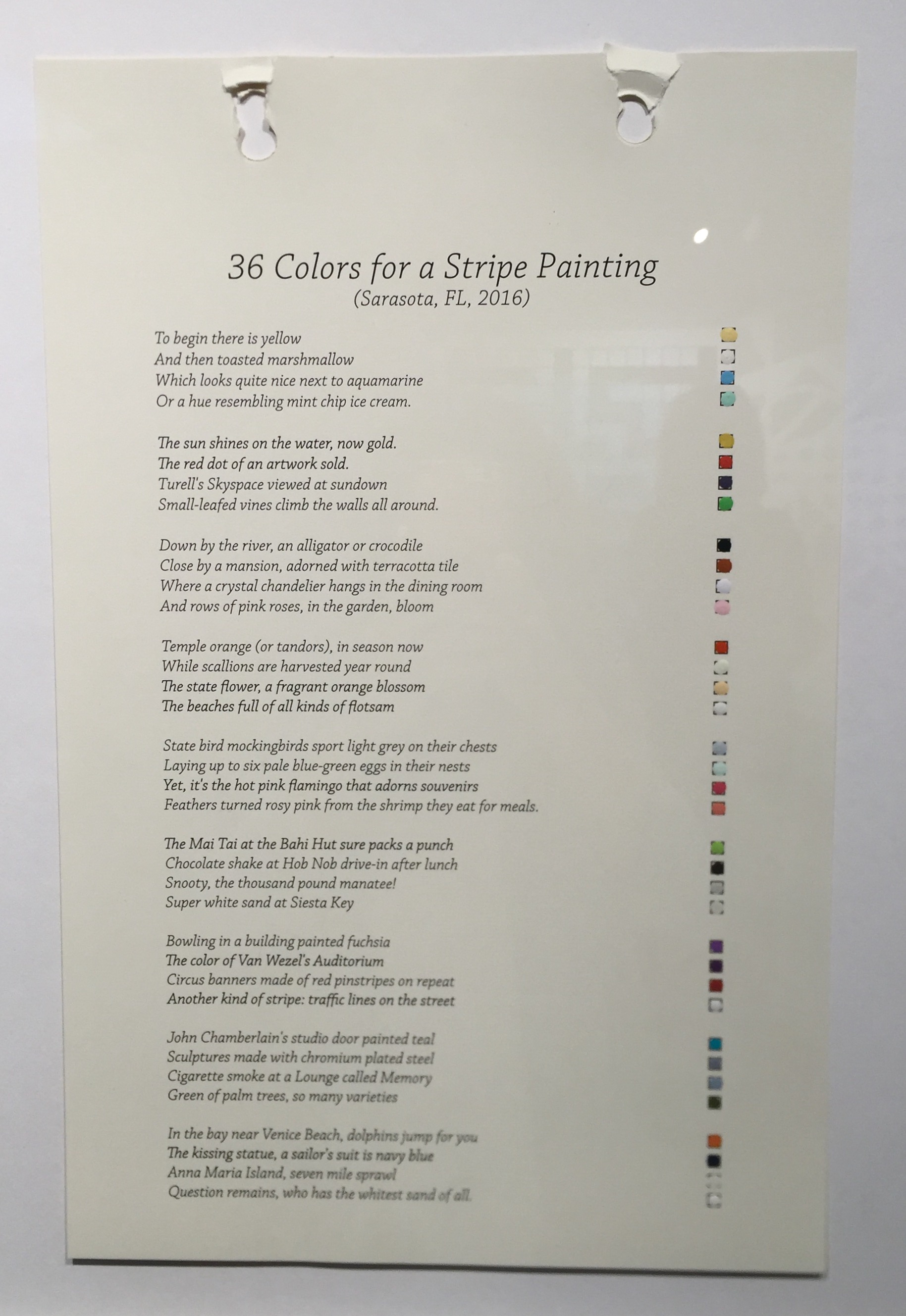

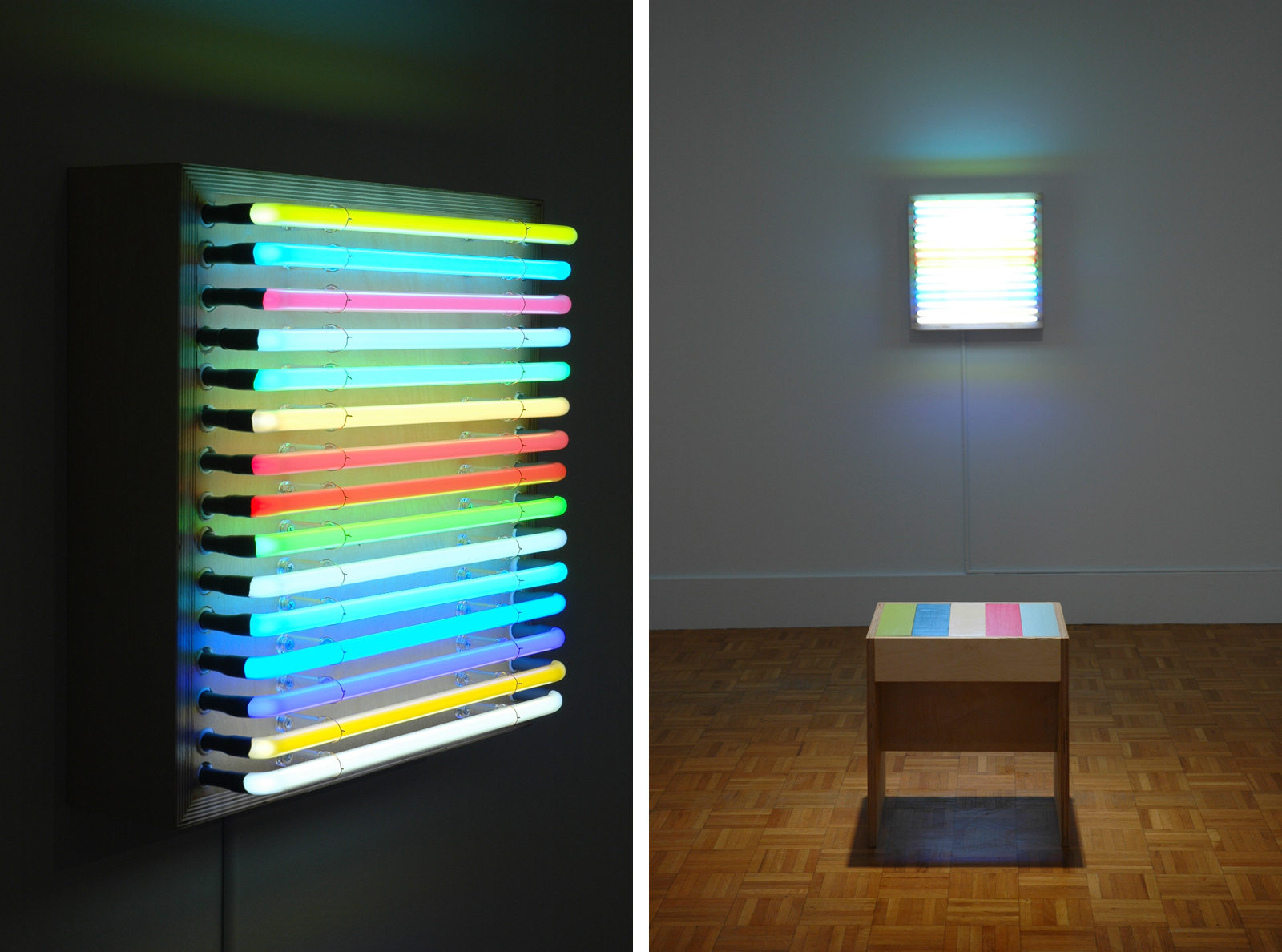

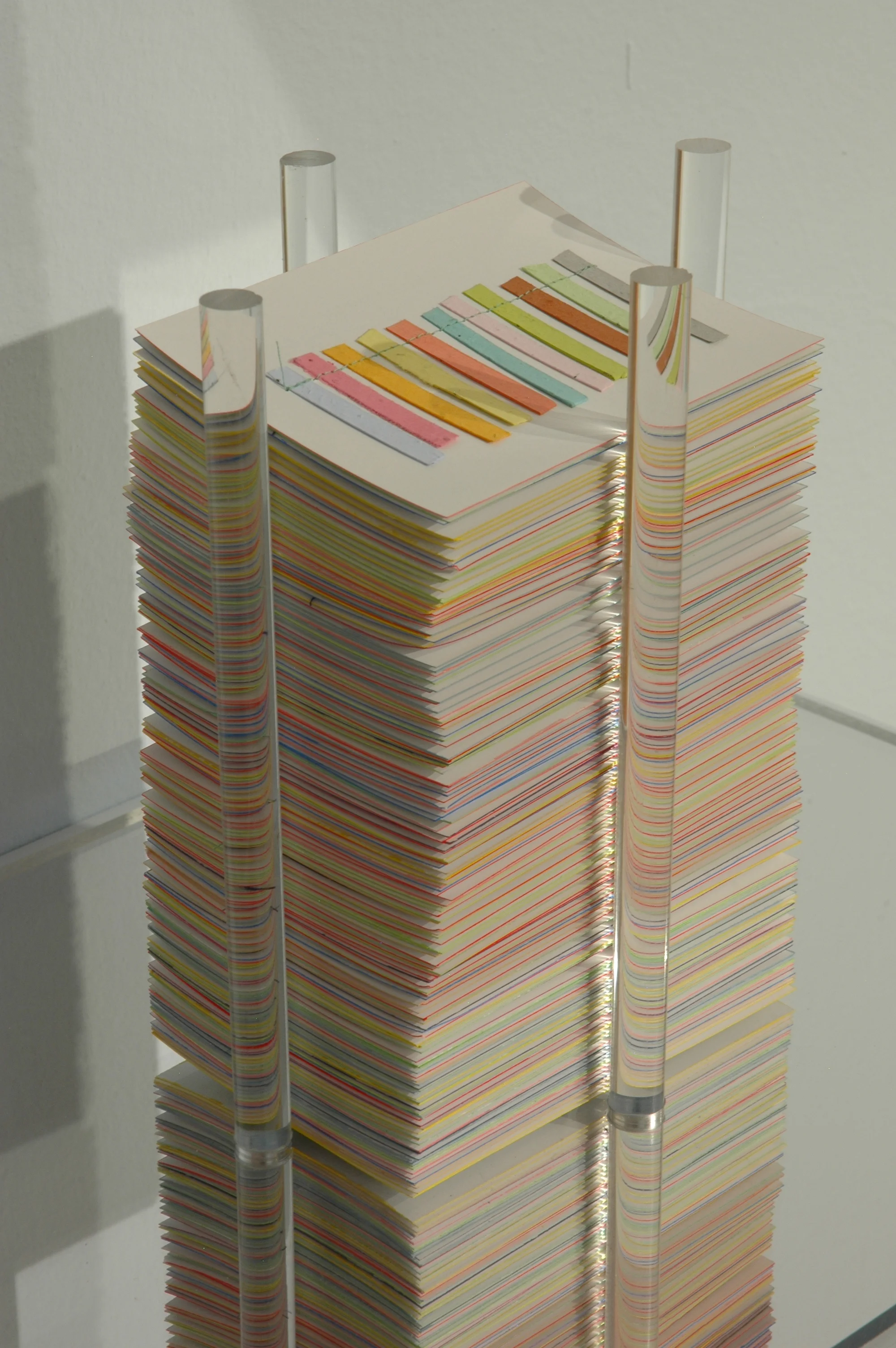

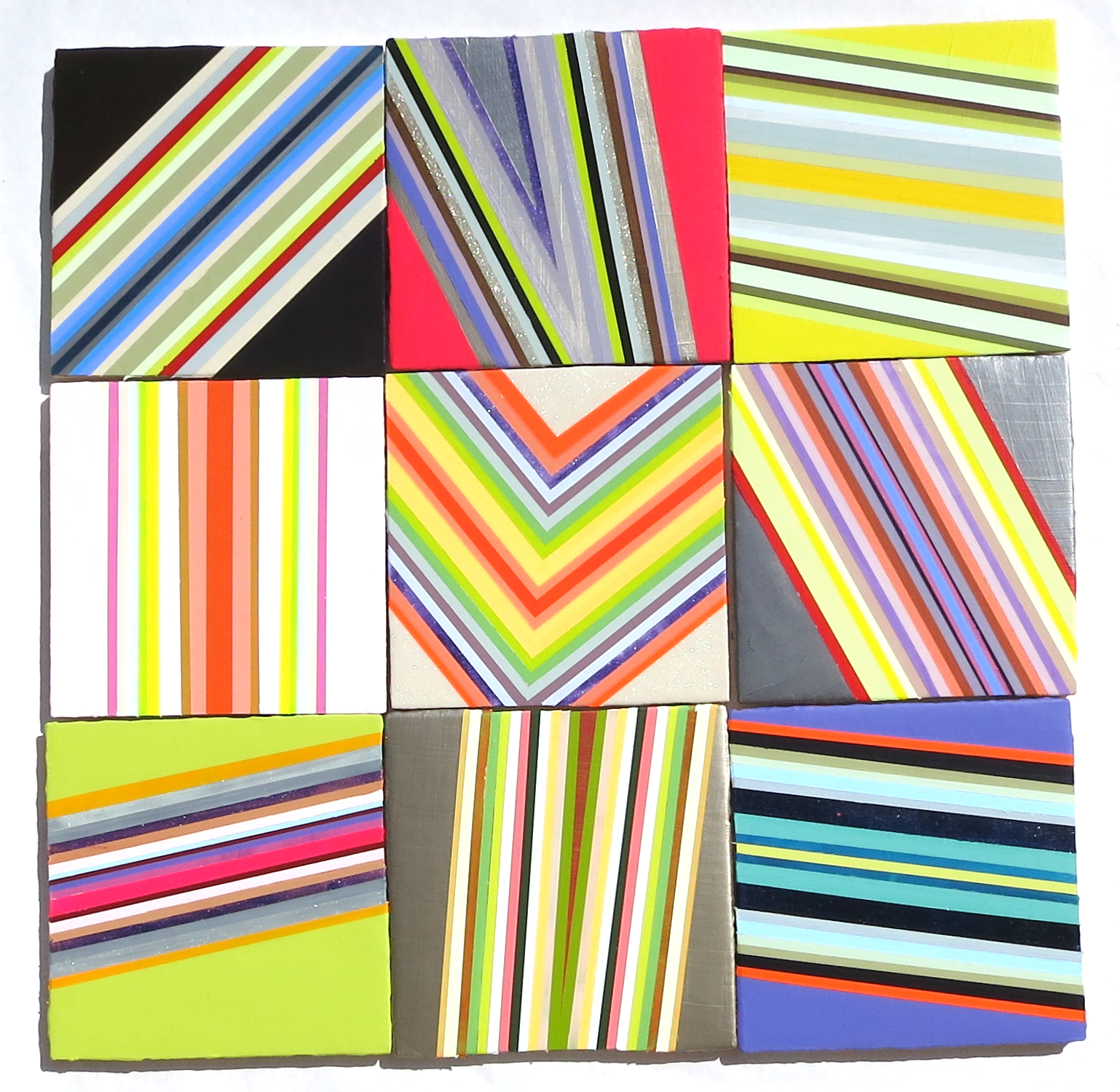

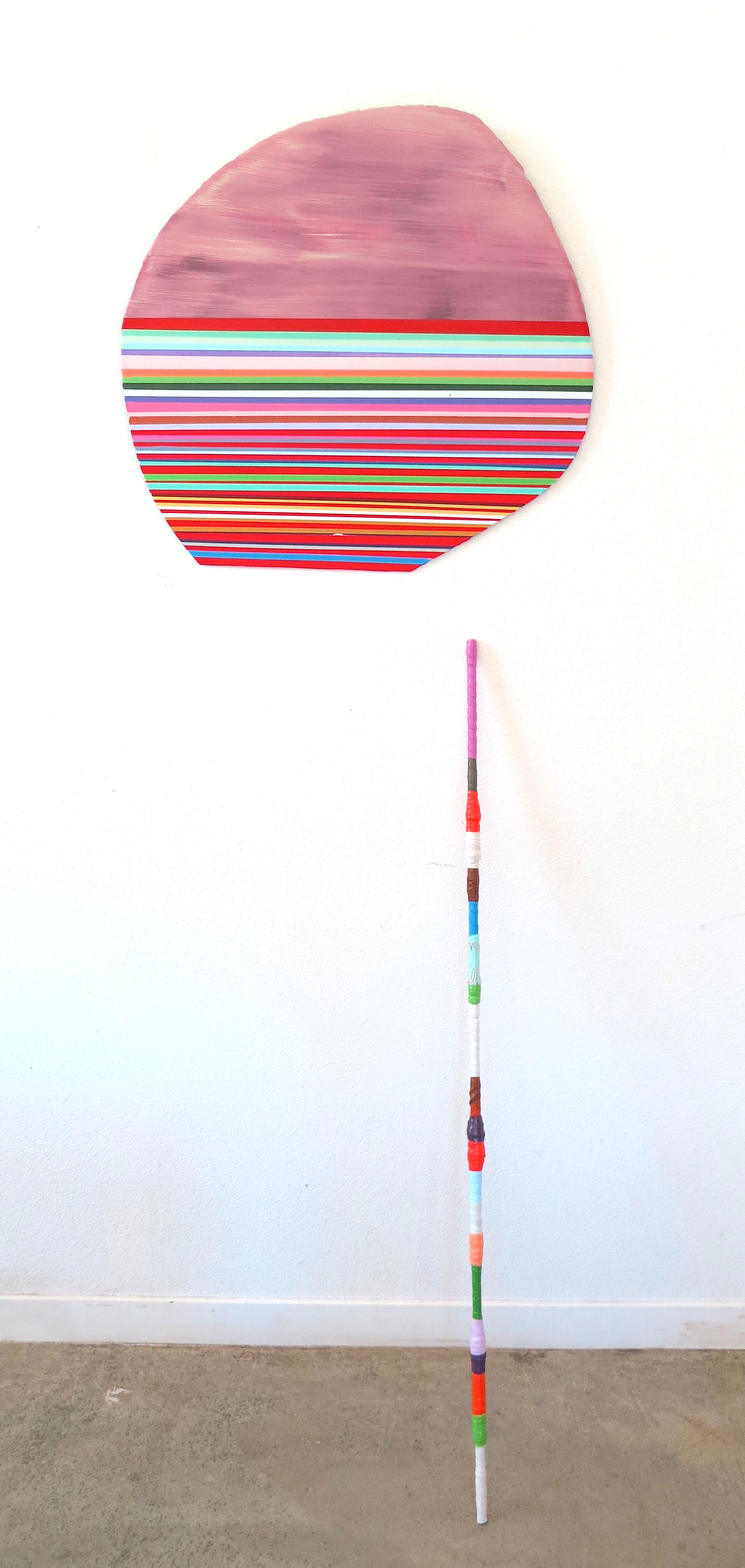

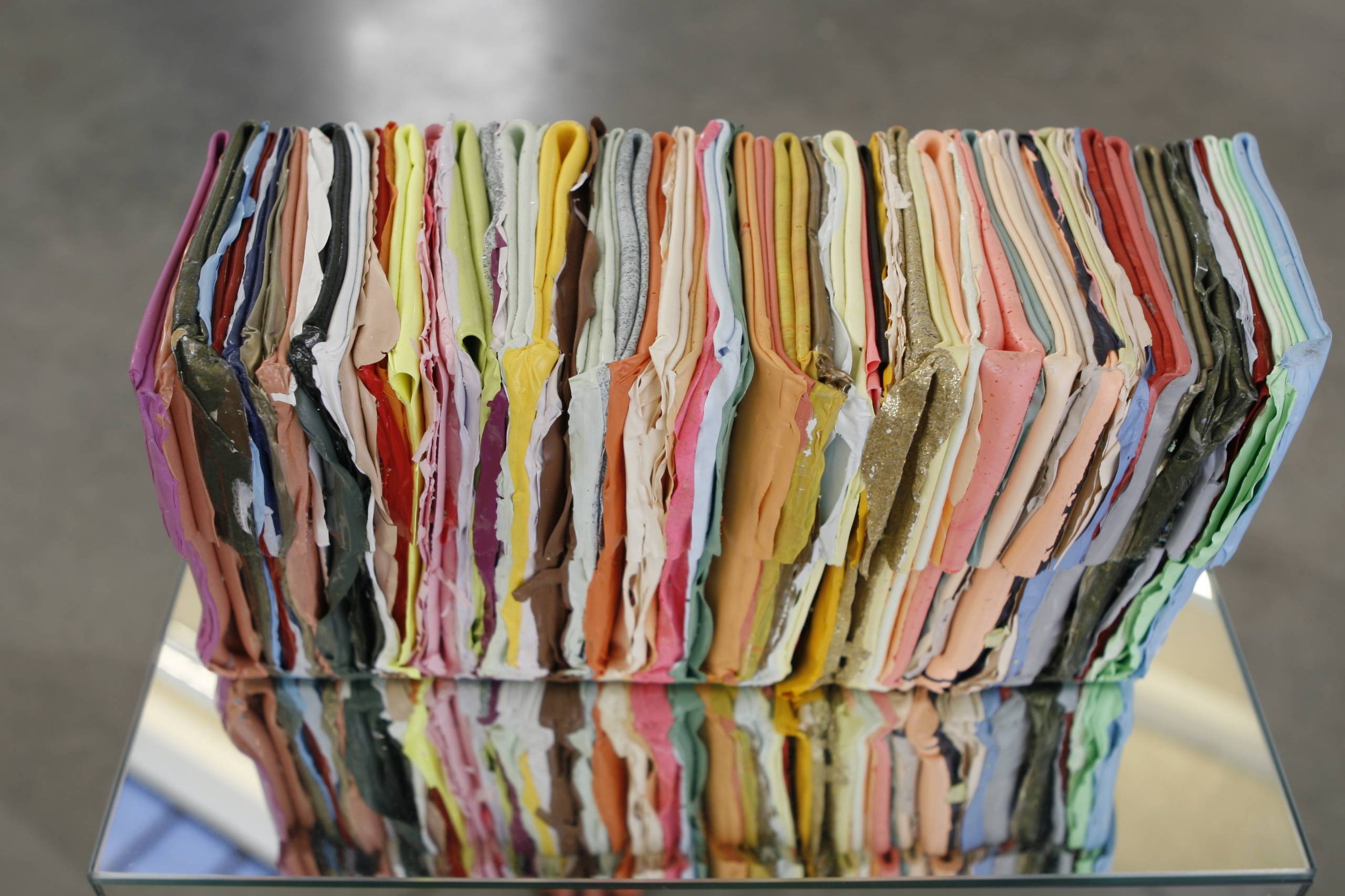

In paintings, sculpture and installations often involving cake, Leah Rosenberg has experimented with methods of accumulation and removal that hide and reveal at the same time, requiring viewers/participants to think about the act of ‘consuming’ art in unexpected ways. The stripes on her paintings are the margins of consecutive layers, one laid over the next as days or weeks pass. In other works, membranes of color freed from any support are stacked into teetering piles or rolled into bundles, becoming objects rather than images. Rosenberg makes these flexible, fondant-like sheets by drying poured paint in stacks of shallow trays, the presence of which gives her studio a kitchen-like ambiance. Some sheets become a kind of wrapping, turning anything (everything?) into a gift.

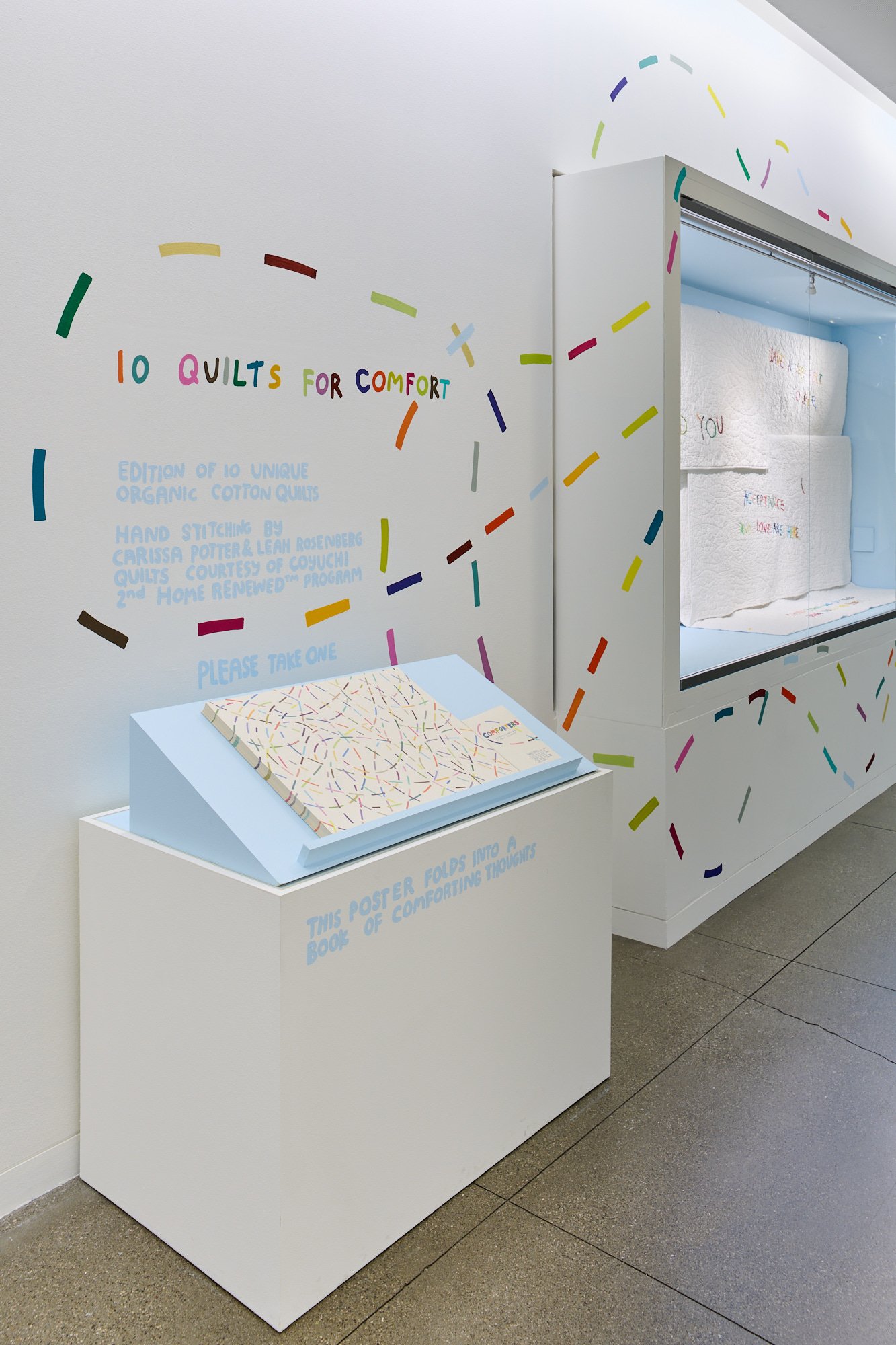

But we are not talking, strictly speaking, of a gift economy here. There is no quid pro quo involved in eating Rosenberg’s cakes. It’s more like xenia, the guest-host relationship described over and over in Homer’s Odyssey—hospitality freely given to the traveling stranger (Rosenberg, raised in Canada, knows first hand about long sojourns in foreign lands), for which the return is more karmic than monetary, more about welcoming generosity than any return of equal value. Although, in a way, what altruists keep secret from the rest of the world is the kind of pleasure and satisfaction that giving itself provides for some-- a thrill that can only be imagined by those of us driven by other impulses.

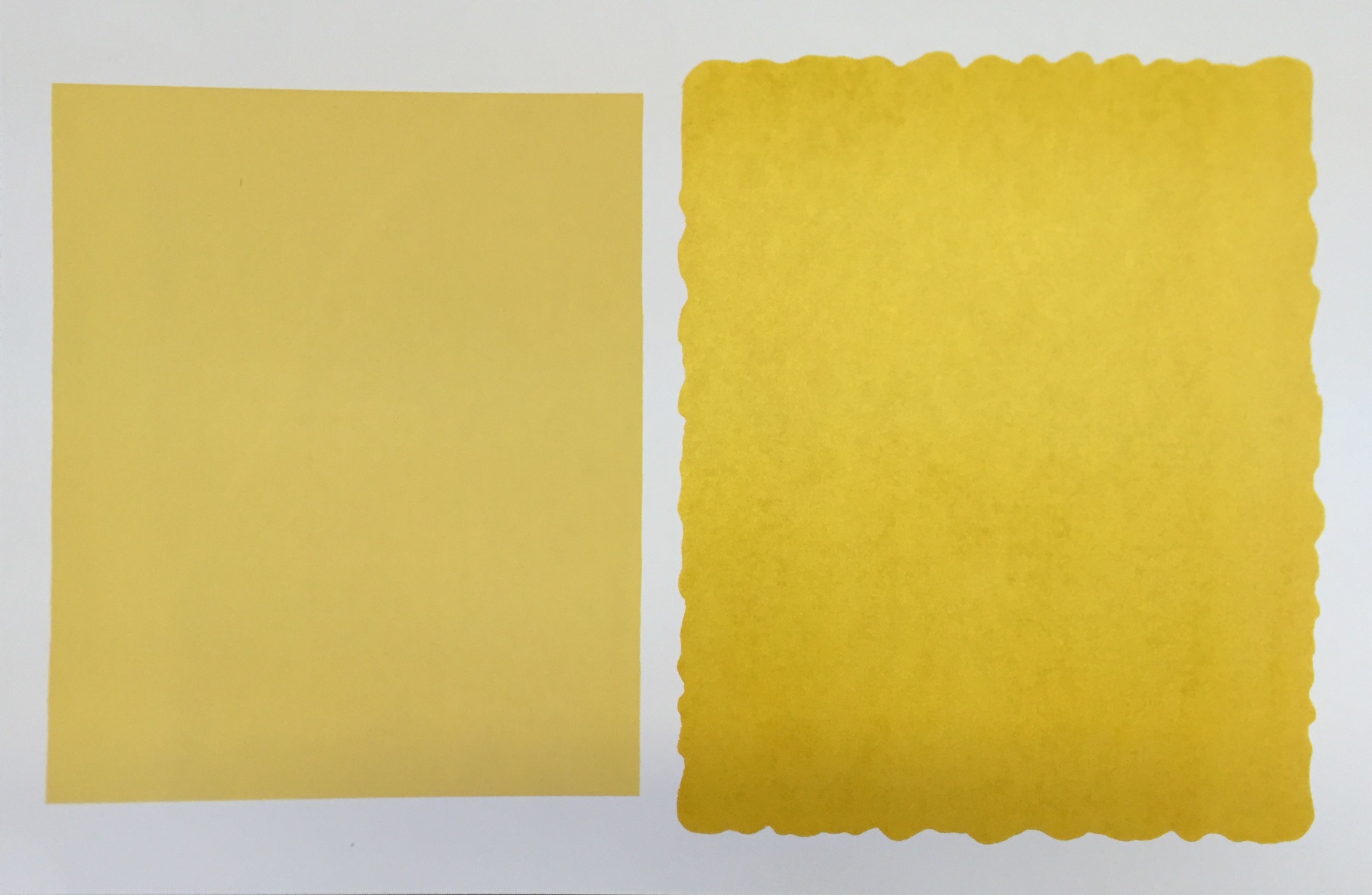

Also central to understanding the way Rosenberg’s ideas operate in a not-always-hospitable world is the idea of something 'looking good enough to eat,' and what that really means, when you think about it. Her experiments with festive tableware; with homemade confetti (remnants of paint sheets patiently punched into tiny circles); with cake on the wall (like a painting) and cake on a pedestal (like sculpture) and with paint itself, stacked like multiple layers of frosting, are all reminders that cake is not, strictly speaking, a food, but the embodiment of a ritualized giving. Are we guests, when we look at art in the usual fashion, as visitors to galleries or museums? Or are we just consumers, who will end up in the gift shop, buying postcards to fill our hunger for something to take home, to own? And if art involves cake, are we satisfied? Is looking at art an experience of celebration, an experience of consumption, or an occasion for gift-giving (or receiving)?

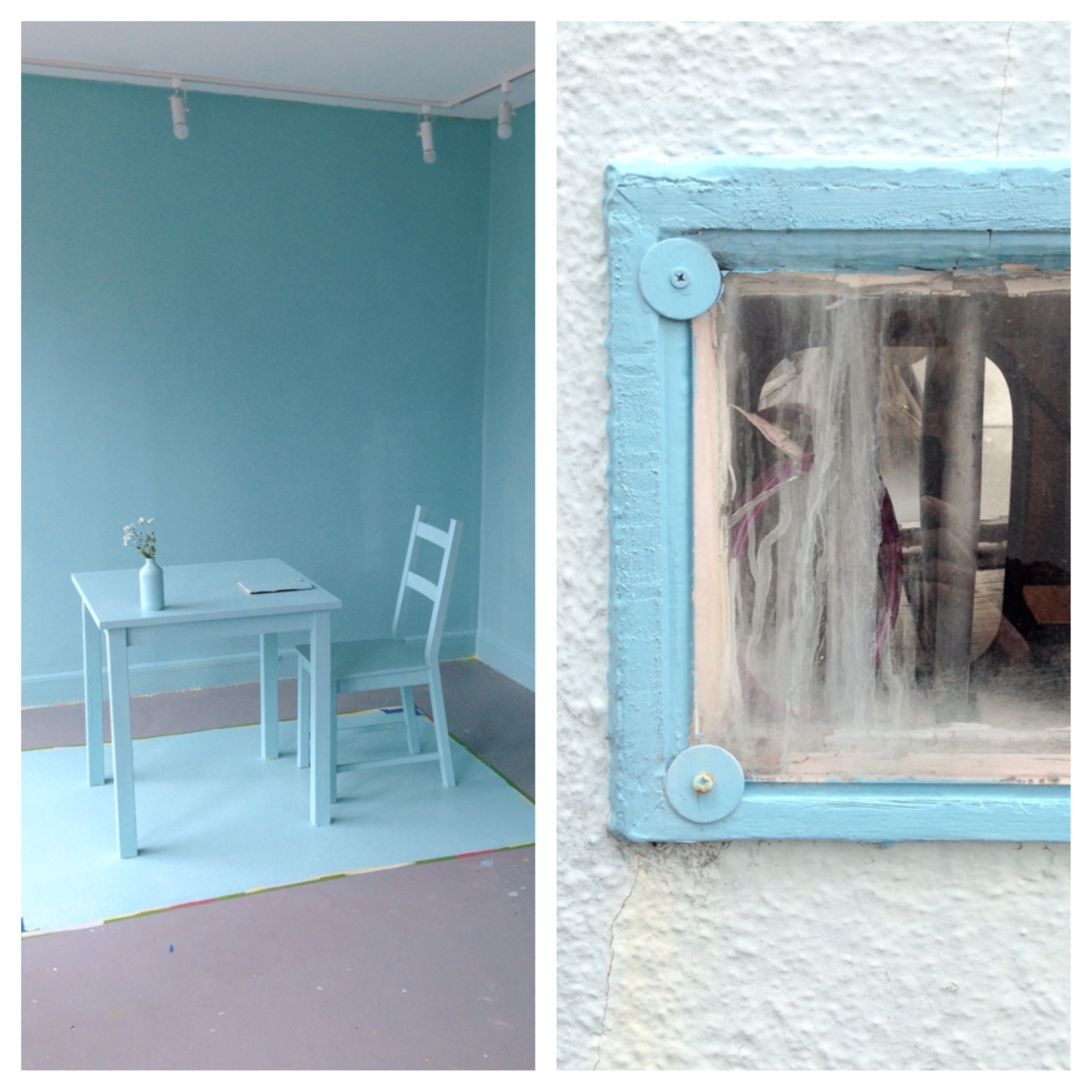

For me, the cinema is not a slice of life, but a piece of cake.—Alfred Hitchcock

The commercial gallery is an ideal site for the exploration of this complicated relationship between art and life, giver and receiver, pitcher and catcher, host and guest. Most of us go to such places mostly to look, but if a certain percentage of visitors don’t come away with a commodity paid for in money, the gallery must eventually close its doors. All guests are welcomed (though only some, into the back room. As with the layers of color buried within Rosenberg’s canvases, a lot remains hidden). By slicing and serving cake, she both confronts that transactional anxiety that gallery-goers often feel and at the same time makes it clear that there are ways in which the artist can take control of the situation in which (s)he is so often powerless.

And what about those swags of mouth-watering color, cascading from the wall, or hanging on nails like clothes or towels? When is painting just paint? When is art really just life? Can either of these ever be true, if the place in which we meet them declares their identity to be something else? Freshness is a quality idolized in the art world. It is possible, then, that there is a tiny private joke being made here, at the expense of that cult-of-the-new, as we are reminded how ‘fresh’ is also a descriptor used in conjunction with appetizing, just out of the oven, delicious, while ‘paint’ is not—in any situation that I can conceive of—edible.

In the end, the cakes Rosenberg makes and serves can be understood as Proustian madeleines, invoking ritual foods eaten at seders or Christmas dinners, each one freshly-made, but composed of uncountable layers of time, shared beliefs or feelings. Though the deeply satisfying layers of her paintings and sculptures can be consumed without caloric guilt, they too are reminders of Lewis Hyde’s injunction that “the gift must always move--” that celebration literally means to engage in ceremonies of rejoicing, respect, festivity: sharing pleasure and affection, understanding and fun. That, in other words, the roles of guest and host are interchangeable, if we want them to be. Let us all eat cake.

Maria Porges